| |

|

|

| |

The Norfolk Island Bug.

Mon 10th December, 2012

|

|

|

|

Life is full of surprises and our two week stay on delightful Norfolk Island was one of them. This small subtropical paradise lies in the South Pacific around 1500 kilometers from Brisbane and is a popular destination for Ozzie holiday makers. The short hour and forty five minute hop from Auckland ensures it also gets its fair share of Kiwi visitors and there were only a few empty seats on our outgoing flight. The quiet, easy going vibe of the island has a reputation for attracting older visitors

{ like Ross } and many return time and time again. I don't blame them because this is one of those places that can really get under your skin ... but its not for everyone. Very little goes on after 10.00pm and there is no night life, no thumping music, no late night bars ... nothing except the sound of the ocean and a big sky overhead ... perfect. During the day there's plenty to keep you occupied and the visitors information center displays a list of " 101 things to do on Norfolk Island ".  This includes kayaking, reef walking and snorkeling, diving, horse riding, archery and some excellent fishing for a variety of species. This includes kayaking, reef walking and snorkeling, diving, horse riding, archery and some excellent fishing for a variety of species.

If you want a chance of a big snapper this is the place to come with some huge fish caught over the years. But book your boat fishing trip well in advance because there are only a few charter skippers operating on Norfolk. There are also some beautiful coastal and forest walks with sites of interest well signposted and plenty of information boards along the way. Most of the accommodation also includes a car but you have to pay the insurance which costs about twenty bucks a day. Its a tiny island only 5 miles long and three miles wide with an extensive road system crisscrossing the whole place. There are some fairly steep hills and no public transport so don't convince yourself that you'll manage without a car. Remember to that cows and geese have right of way and there is also a healthy population of feral chickens to keep you on your toes. A word of warning, watch out for pot-holes. At the moment Norfolk Islanders don't pay any income tax or road tax so their highway maintenance department is a bit basic. Just a couple of guy's who drive around with a container of hot tar and some gravel on the back stopping every so often to fill up a hole. They must have been on holiday when we were there because things were a getting bit behind and some of the unfilled holes were real axle breakers which made driving "interesting". There are some fairly steep hills and no public transport so don't convince yourself that you'll manage without a car. Remember to that cows and geese have right of way and there is also a healthy population of feral chickens to keep you on your toes. A word of warning, watch out for pot-holes. At the moment Norfolk Islanders don't pay any income tax or road tax so their highway maintenance department is a bit basic. Just a couple of guy's who drive around with a container of hot tar and some gravel on the back stopping every so often to fill up a hole. They must have been on holiday when we were there because things were a getting bit behind and some of the unfilled holes were real axle breakers which made driving "interesting".

It all adds to the undoubted charm of the place and is like going back in time.

For instance there are no traffic lights and only one roundabout. Not that the roads were exactly gridlocked. Even during the peak season there's only a total of around three thousand people on Norfolk including the locals.

Gail and I never usually bother with organised trips but part of the deal was a free half day tour and we have to admit we actually enjoyed it and were glad we went along.

For such a small place there's a lot to see and do and Dennis our guide was keen to point these out so that we could visit them ourselves another day. Without this we'd have wasted a lot of time and missed out on some spectacular sight seeing and photo opportunities.

The whole island is awash with history that dates back to the first Polynesian settlers in the fourteenth century. Research suggests they probably came from the Kermadec Islands to the north of New Zealand or even from North Island itself. The site of their main village was discovered at Emily Bay and during its excavation various artifacts including stone tools were found. These early inhabitants lived on the island for several generations before they mysteriously disappeared and were responsible for introducing the New Zealand flax, banana trees and the Polynesian Rat. No one knows what happened to these original settlers and it remains an unsolved puzzle to this day.

The first European sighting of Norfolk Island is attributed to Captain James Cook aboard HMS Resolution on his second voyage to the South Pacific in 1774. Cook had set sail from England in 1772 and he named the island after the Duchess of Norfolk. But what he didn't know at the time was that she had died in May 1773. Cook and his landing party went ashore on Tuesday the 11th October 1774 and this is described by Andrew Kippis who was documenting the voyage :

" As the Resolution pursued her course from New Caledonia, land was discovered, which, on a nearer approach, was found to be an island, of good height, and five leagues in circuit. Captain Cook named it Norfolk Isle, in honour of the noble family of Howard (Fn.: It is situated in the latitude of 29° 2' 30" south, and in the longitude of 168° 16' east). It was uninhabited; and the first persons that ever set foot on it were unquestionably our English navigators. Various trees and plants were observed that are common at New Zealand; and in particular, the flax plant, which is rather more luxuriant here than in any other part of that country. The chief produce of the island is a kind of spruce pine, exceedingly straight and tall, which grows in great abundance. Such is the size of many of the trees that, breast high, they are as thick as two men can fathom. Among the vegetables of the place, the palm-cabbage afforded both a wholesome and palatable refreshment; and, indeed, proved the most agreeable repast that our people had for a considerable time enjoyed... "

On Cook's return to England he took back plant samples including the New Zealand flax and reported :

" except for New Zealand, in no other island in the South Sea was wood and mast-timber so ready to hand ".

Today his reputed landing site is over-looked by a popular visitor attraction and picnic spot known simply as " Captain Cook " and is a great place to enjoy a BBQ. According to our guide, their initial excitement on first sighting the Norfolk pine and its possible use as mast timbers for the Navy proved a disappointment. Although the tree does grow exceptionally straight and tall, the branches form knots right through the trunk which creates weak spots along its length, not ideal in a ships mast. But they were unaware of this problem then and combined with the abundance of New Zealand flax { from which they thought they could weave the fibers to produce sail-cloth } made Norfolk Island an important source of ship building materials. These two commodities were needed to maintain British sea-power and later after the American War of Independence the usual supply of this timber from New England dried up. At the same time during treaty negotiations Catherine II of Russia tightened her control of the supply of hemp and flax through Russian ports, thus depriving Britain of the materials to make ropes and sails for its ships. This and increasing French interest in the South Pacific hastened the decision by the British Government to gain a presence in the area and in 1786 plans were finalized for a dual colonization of Norfolk Island and Botany Bay. Today his reputed landing site is over-looked by a popular visitor attraction and picnic spot known simply as " Captain Cook " and is a great place to enjoy a BBQ. According to our guide, their initial excitement on first sighting the Norfolk pine and its possible use as mast timbers for the Navy proved a disappointment. Although the tree does grow exceptionally straight and tall, the branches form knots right through the trunk which creates weak spots along its length, not ideal in a ships mast. But they were unaware of this problem then and combined with the abundance of New Zealand flax { from which they thought they could weave the fibers to produce sail-cloth } made Norfolk Island an important source of ship building materials. These two commodities were needed to maintain British sea-power and later after the American War of Independence the usual supply of this timber from New England dried up. At the same time during treaty negotiations Catherine II of Russia tightened her control of the supply of hemp and flax through Russian ports, thus depriving Britain of the materials to make ropes and sails for its ships. This and increasing French interest in the South Pacific hastened the decision by the British Government to gain a presence in the area and in 1786 plans were finalized for a dual colonization of Norfolk Island and Botany Bay.

The illustration above is taken from the journals of William Bradley entitled "A Voyage to New South Wales" Dec 1786 - May 1792. He served in the Royal Navy for over 40 years and sailed with the First Fleet to Botany Bay. He was appointed First Lieutenant on the ill-fated HMS Sirius in October 1786. Sirius the flag-ship of the fleet foundered on the reef at Norfolk Island's Slaughter Bay while attempting to land supplies in March 1790. Most of the artifacts from the wreck are displayed at the Norfolk Island Museum. The descriptions below of the first and second settlements established on the island are from the web-site created by Norfolk Island's Society of Pitcairn Descendants.

The First Settlement

" On March 6, 1788, the British colours were raised over Norfolk Island.

Six weeks earlier, Britain's First Fleet had arrived at Botany Bay (soon to become Sydney) to establish the penal colony of New South Wales. Hand picked from the ranks of the First Fleeters were 23 settlers: 7 freemen, 15 convicts and the commandant, Lieutenant Phillip Gidley King. The occupation of the island was to serve two ends: to make available masts and sails from pine and flax for the refurbishment of British ships, and to prevent the island falling into the hands of His Majesty's rivals, the French. The occupation suffered initial setbacks, but began to flourish. Ground was cultivated, crops planted and harvested; the settlement became a tiny township.

In March of 1790, Norfolk Island received some 300 new people to its shore, and the reef its first British ship. The ships "Sirius" and "Supply" had brought two companies of Marines plus new convicts from Sydney, where dwindling supplies of food had become a serious problem. The 540-ton " Sirius" and most of its provisions were lost on the coral reef.

The continuing influx of convicts from Sydney during the following few years saw Norfolk Island become nothing more than a labour camp for Sydney's most difficult officers and least-wanted felons. The island's main purpose was to provide food for Sydney. Maize, wheat, potatoes, cabbage, timber, flax and fruit of all kinds grew well in Norfolk Island. The population peaked at more than 1,100, and about a quarter of the island was cleared.

But by 1814 the island was empty. Sydney and the expanding colony of New South Wales had no further need to import food from Norfolk; the people who had occupied it were shipped back to New South Wales. The structures of the settlement were razed or pulled down stone by stone in order to dissuade passing ships from reoccupying the island - and to make the island less alluring for escaped convicts. The farm and domestic animals were shot, though wild dogs were left to scavenge.

Norfolk Island began to heal its scars. Trees grew to their former splendour; rain washed away the blood of the flogging yard; plants grew over the stone of the ruined buildings; and the sound of the lash on convict back was not heard again.

Until, that is, 11 years later when Norfolk became the Hell of the Pacific ".

The Second Settlement

" During Norfolk Island's second settlement (between 1825 and 1855) it was indeed the Hell of the Pacific; a place dominated by death and despair.

In 1824 the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Brisbane, received a directive from the British Secretary of State to the effect that Norfolk Island was to be turned into a penitentiary once again. Because of the island's inaccessibility, Brisbane decided that it was the best place to send the worst felons "forever to be excluded from all hope of return". Norfolk Island would be "the ne plus ultra of Convict degradation", "a place of the extremest punishment short of Death."

For many death was welcomed. Conditions in the gaol were appalling; a large percentage of the convicts were sentenced to remain in heavy chains for the terms of their natural lives; most convicts were chained during the day. Agricultural labour was the most hated kind; chain gangs were forced to hoe from sunrise until sunset. One convict in a field gang raised his hoe and split the head of the convict in front of him - not through malice or revenge, but to be hanged, to be free of a life worse than death. Why not suicide? Simply because most of the convicts were Catholics - a fact testified to by the cemetery's headstones.

Punishments were varied for petty crimes during this second occupation. Lashings were common: sometimes up to 500 strokes. Dumb-cells were constructed to exclude light and sound; many men lost their sanity in them. Solitary confinement, increased workloads and decreased rations - sometimes bread and water - were also common forms of punishment. One documented case concerns a convict by the name of Micheal Burns who suffered a total of 2210 lashes and almost two years in confinement, much of it in solitary, three months of that in total darkness, and at least six months of those two years on a diet of bread and water only. Burns' crimes? Insolence, suspected robbery, neglect of work, striking a fellow prisoner, bushranging, singing a song, calling for a doctor, attempted escape, and inability to work due to the debility caused by his punishments

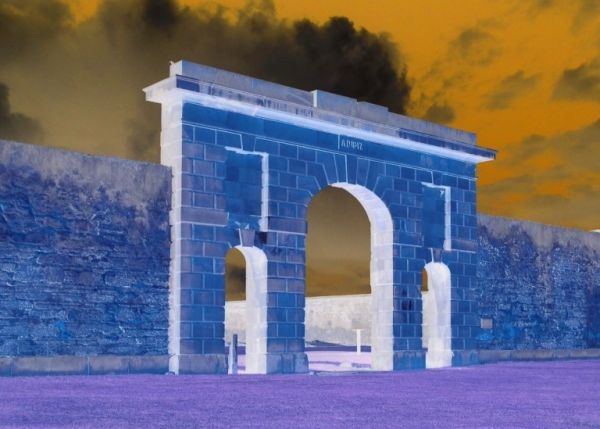

Convicts were also forced into hard labour as a form of punishment building much of what today is one of the world's chief glories of Georgian architecture - Kingston, Norfolk Island. Stone was quarried from Nepean Island, a rock close to shore, and coral rubble was rendered with lime and sand; thus most walls were formed, while Norfolk Pine was used for joinery and roofs. Floors were made from thin stone slabs.

During the late 1840s and early 1850s a number of influences led yet again to the abandonment of Norfolk Island. The cost of maintaining the penal settlement was growing; more than 1200 convicts were gaoled on the island, and Port Arthur in Van Dieman's Land (now Tasmania) was viewed as a less costly alternative. Dr Robert Wilson, Catholic Bishop of Hobart, wrote a damning report on the practices he witnessed on a visit to Norfolk Island, and called for its abandonment. A number of days before his visit 34 men were flogged; the day after his arrival, another 14; and at the service he held on the island, 218 of the 270 men attending were in chains. Last but not of least importance Earl Grey back in the British Parliament saw Norfolk as a possible home for the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island - the descendants of the mutiny on the "Bounty" and their Tahitian-Polynesian wives.

By 1855 the island stood empty once more. Never again would it bear witness to penal cruelty and inhumanity. And shortly it would receive the people who still call Norfolk Island their homeland - and who fight for the right to govern themselves ". Lots more interesting information at : www.pitcairners.org

Norfolk Island is probably most famous for its connection with Fletcher Christian and the Mutiny on the Bounty. His name along with those of others involved can be seen all over the island and one of the staff at our accommodation was a direct descendent of Christian himself.

After the mutiny several of the mutineers together with their Tahitian wives { and a few Tahitian men and women } eventually found Pitcairn Island on the 17th January 1790. The tiny 450 hectare island had been wrongly charted and they decided this would be an ideal place to hide from the inevitable consequences of their actions once news of the mutiny reached England.

They remained on the island undiscovered until an American whaler came across them in 1808. By then murder or suicide had claimed the lives of eight of the nine mutineers and only one ... John Adams was left alive. Under his leader-ship the small community thrived. Six years later in 1814 two British ships the " Tagus " and " Briton " accidentally found them again. Although the captains of both vessels reported back to the British authorities the government had by then lost interest in any form of retribution and they were left alone.

In 1825 another British ship arrived and formerly granted Adams amnesty but by now the Pitcairn community was rapidly outgrowing their tiny home. After a failed attempt at living on Tahiti they again petitioned the British Government to relocate them. With the infamous penal colony now closed and the place abandoned they were offered Norfolk Island. On June 8th 1856 194 men, women and children along with all their possessions arrived at Norfolk Island and occupied the remains of the penal settlement. Not all of them stayed, during the early years some returned to Pitcairn where there is still a small community. Those that decided to remain gradually established farms and also became involved in the whaling industry influenced by American whalers who began calling at the island to re-supply. Over one third of the island's current population are descended from the settlers who arrived from Pitcairn. Each year on June 8th the islanders dress in period costumes and celebrate what they call Bounty Day with a re-enactment of the landing together with the laying of wreaths in memory of the settlers of 1856, this is followed by a community party and sports day. Norfolk Islanders are extremely proud of their heritage and culture which they're eager to share with visitors and there are all kinds of excursions and themed entertainment available. The Pitcairners also brought with them their own language now called " Norfuk ", a mixture of 18th century English and Tahitian which although in decline is still in use to this day despite being one of the rarest languages in the world.

But without a doubt it was Norfolk's strategic position in the South Pacific and the decision to build an air-strip during World War Two which has had the biggest impact on the island and its inhabitants. It opened up this beautiful destination to the outside world and tourism quickly flourished becoming the driving force behind the Norfolk economy. Although some visitors arrive by sea from cruise ships which anchor outside the reef, the majority travel by air and there are currently three flights a week from Australia and one from New Zealand. Over the years the island has attracted television crews from all over the place. And as we sat in departure I spotted Graeme Sinclair and his " Gone Fishin " production team also waiting to board the return flight to New Zealand. Unfortunately the global down-turn in the tourism industry is having an effect on the islands economic future and they are experiencing tough times. Even so from the moment you get there your made to feel right at home. They welcome visitors with open arms and its one of the friendliest places we've ever been too. As I mentioned earlier it isn't for everyone but if you enjoy a laid back, do as little or as much as you like, beachy sort of holiday, in the middle of nowhere with good food and fantastic scenery, this is the place. We've definitely been bitten by the Norfolk Island bug and before we left booked again for next year, something that we've never done on any other vacation. But without a doubt it was Norfolk's strategic position in the South Pacific and the decision to build an air-strip during World War Two which has had the biggest impact on the island and its inhabitants. It opened up this beautiful destination to the outside world and tourism quickly flourished becoming the driving force behind the Norfolk economy. Although some visitors arrive by sea from cruise ships which anchor outside the reef, the majority travel by air and there are currently three flights a week from Australia and one from New Zealand. Over the years the island has attracted television crews from all over the place. And as we sat in departure I spotted Graeme Sinclair and his " Gone Fishin " production team also waiting to board the return flight to New Zealand. Unfortunately the global down-turn in the tourism industry is having an effect on the islands economic future and they are experiencing tough times. Even so from the moment you get there your made to feel right at home. They welcome visitors with open arms and its one of the friendliest places we've ever been too. As I mentioned earlier it isn't for everyone but if you enjoy a laid back, do as little or as much as you like, beachy sort of holiday, in the middle of nowhere with good food and fantastic scenery, this is the place. We've definitely been bitten by the Norfolk Island bug and before we left booked again for next year, something that we've never done on any other vacation.

I'm back on the river this week so next time a proper fishy report. I hear there are some better browns around and with the weather looking good for the week ahead it'll be nice to have a chuck.

Tight lines guys

Mike |

|

|

| Back to Top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|